Risk & Progress| A hub for essays that explore risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future. Subscriptions are free, paid subscribers gain access to the full archive, including the Pathways of Progress and Realize essay series.

Previously, I explored some of the merits and drawbacks of patents and prizes to incentivize innovation. I arrived at the uncomfortable conclusion that patents, while highly imperfect, cannot be completely abolished and replaced with awards. That said, there is room for improvement to the existing IP system. Here we look at some novel proposals for how we might rethink intellectual property and sharpen the blade of innovation for the 21st century.

Economic theory holds that the free market will naturally underinvest in science and innovation. Our global “social supercomputer” will undersupply new ideas because it’s cheaper and less risky to copy than it is to innovate. Furthermore, basic research, which has no clear return on investment, is largely neglected. This is because ideas are non-rivalrous. My use of an idea doesn’t prevent anyone else from also using it. Thus, to give an idea marketable value, we must enclose it behind a metaphorical “fence.” In essence, we create artificial scarcity through what we call “intellectual property.”

I won’t rehash the many problems with patents, but I want to emphasize that the current IP system can prevent the efficient use of ideas. Patents can give rise to what we previously explored as the “Tragedy of the Anticommons.” As you recall, the Tragedy of the Commons occurs when shared ownership results in underinvestment and overuse of a resource. On the other hand, the Tragedy of the Anticommons describes a circumstance where ownership is divided, resulting in the underuse of a resource, in this case, an underuse of ideas. A patent dispute between the Wright Brothers and Glen Curtis, for example, stymied aircraft technology in the US until the government intervened at the outset of World War 1.

Some have suggested we could abandon IP entirely. During World War 1, under the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act, US authorities confiscated all German-owned US patents and made them available for compulsory licensing. Researchers found that counter to prevailing theory, the compulsory licensing scheme was associated with a ~20 percent increase in innovation by affected German and American firms. That said, the scheme was a one-off wartime event; should compulsory licensing have remained law, innovation likely would have been depressed.

In his book, Launching the Innovation Renaissance, Alexander Tabarrok also questions the utility of patents. Tabarrok noted that humans have been breeding and registering new types of roses for thousands of years. It was only after the 1930 Plant Patent Act that breeders gained the ability to patent breeds. Therefore, the theory holds, that after 1930 we should find a surge in new patented rose breeds. We don’t; over 80 percent of new breeds created thereafter were unpatented. Roses are not unique in this regard, indeed, most ideas of all shapes and varieties are not patent-protected, and innovation marches along just fine, if not better, without them.

There are, however, areas where patents do appear to stimulate innovation. One such area is pharmaceuticals where it may cost over a billion dollars to develop a new drug, while just a few cents to produce each pill. Here, patents have an outsized impact because of the high initial capital investment and low marginal cost of production (and replication). The Orphan Drug Act, for example, gave sponsors of drugs for rare diseases seven years of market exclusivity. The act led to a boom in the development of new lifesaving drugs.

Tabarrok concludes that the disconnect between theory and practice lies in the fact that, over time, we have become much more liberal in what allow to be patented. In times past, a tangible product had to be successfully demonstrated before a patent could be granted. Today, on the other hand, an intangible idea alone will suffice, and these ideas can be frustratingly broad. He points to the infamous “E-data” patent, granted in 1983, which covered everything from downloading photos, music, and other files. Creators were forced to pay royalties to E-Data for what was essentially a vague idea, not a technology. Tabarrok writes, “Edison famously said, "Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration." A patent system should reward the 99 percent perspiration, not the 1 percent inspiration.”

Tabarrok recommends splitting patents into terms of varying lengths based on the level of “sunk costs.” An idea or innovation with low costs could easily apply for, and be granted, a short-term patent. However, long-term patents would be subject to higher scrutiny, requiring evidence to show that the innovator expended a great sum of resources to develop the idea. Taking a page from Tabarrok, I envision a two-tier patent system with 2-year and 20-year patents available to inventors. The 2-year patent would be essentially an extension of a “first mover” advantage in the marketplace, granted for the 1% inspiration. The 20-year patent, on the other hand, would require evidence of sunk costs to reward the other 99 percent.

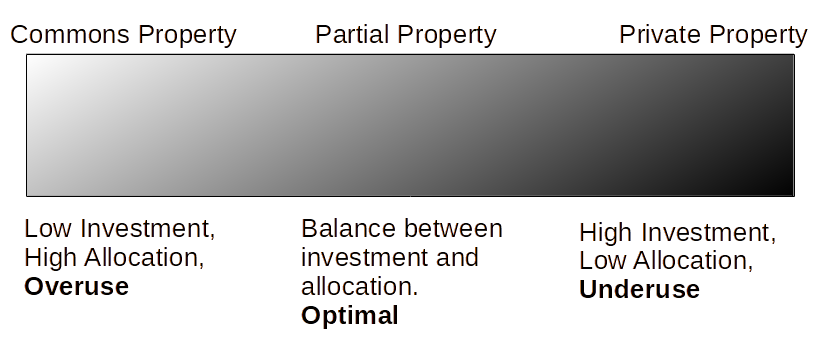

Arguably, this solves many of the problems plaguing the current patent regime by shortening the duration of most patents issued. It does not, however, solve the deadweight loss and allocative efficiency challenges for long-term patents. Remember, I previously argued that there is a “spectrum” of optimal property rights. Common ownership results in high allocative efficiency but low investment incentives. When ownership rights are too strong, however, investment incentives are high but allocative efficiency is low, so the property is not used in the most efficient ways. At both extremes, the result is not optimal. The best property may not be commonly owned or privately owned, but rather a hybrid of both. For IP especially, we can use this continuum to our advantage.

Patents as Probabilities

Ian Ayres and Paul Klemperer propose a radical rethink of IP along these lines: Probabilistic Patents. They argue that an efficient patent policy should provide “constrained” market power, not an absolute one. That is, the government should allow a limited amount of patent infringement that balances returns to inventors with social costs. One means of achieving “constrained” market power is to combine uncertainty with delay of IP enforcement. Probabilistic determination means that some “infringers” will calculate that the risk of violating a patent is worth the potential profit. A few “infringers” will enter the marketplace and curtail the monopoly power of the patent holder. Only a limited number of players would step in because the market would naturally reach a point where the risk of “infringement” would outweigh the profit potential. Thus, competition would be limited and would not wipe out the patentholder’s profits or their incentive to innovate.

Ayres and Klemperer illustrate how a small amount of uncertainty reduces deadweight loss (the aforementioned social costs of patents) by much more than it reduces the patentees’ expected profit. For example, they calculate that if the probability of enforcement is cut to 95%, the market price of the patent is cut by 10% and the social deadweight loss is reduced by over 18%. Would this not reduce the incentive to innovate? It certainly does by a small amount but we can compensate for this by lengthening the patent terms. For example, reducing the probability of enforcement to 90 percent would require lengthening the patent term by just 3.4 percent to achieve the same profits for the patent holder, while reducing the social cost of the patent by roughly 30 percent.

In short, consumers of IP benefit from oligopolistic pricing for a longer period than they do under monopoly pricing for a shorter one. A similar outcome could be achieved through a Duopoly Auction. In that system, a patent would confer not only the right to an idea but also a mandate to auction it off to a second owner. The inventor would still receive profit from its sales alongside a hefty lump sum payment at the patent auction. Consumers would benefit from access to lower-cost duopoly-priced ideas rather than monopoly-priced ones.

A Continuum of Excludability

We don’t need to roll the dice on patent enforcement, however, if we know its value. Determining the value of an idea is difficult because there is natural variation in the degree of excludability. Amy Kapczynski & Talha Syed discussed this “continuum of excludability” in the Yale Law Journal. They note that 30,000 people die every year in ICUs from infections resulting from central-line catheters. The IP system, of course, would reward a company handsomely for developing a new antibiotic that saves these lives. But the solution doesn't need to be a new drug. In fact, the New England Journal of Medicine developed a life-saving innovation that cuts these infections by two-thirds: a simple checklist of standard hygienic and communication practices that can be performed at any ICU at virtually no cost. A patent system would protect and reward the creation of a new drug, but it would struggle to reward the developer of this checklist.

Both inventions have similar social value, but one has greater market value. The reason is the degree of excludability. Even if one could patent the checklist, it would be impossible to monitor the activity of every ICU to ensure that royalties were paid when the system was used. A drug, on the other hand, is highly excludable; the legal system can prevent copies from being produced and sold on the market. Thus, when we discuss the market value of a patent or idea, that value is derived from the social value moderated by the fraction of that value that is excludable in the marketplace. Much of the research on IP tends to focus on pharmaceuticals because they are easily excludable. This does a disservice to other ideas that are less tangible but otherwise have equal or higher social value. Putting this all into a crude formula, the market value (V) is the social value (S) moderated by the fraction of social value that is excludable (C).

V=C(S)

Patent Buyout Auctions

A method for divining a patent’s value was proposed in 1997 by Michael Kremer: patent buyout auctions. In his proposal, an auction is used to determine the value of a patent, whereafter the government buys and open sources it. This concept has some historical precedent. Daguerreotype photography, invented in 1837, was the first means of taking photographs. Recognizing the innovation’s importance, the government of France purchased the patent and placed it in the public domain. Free to use, the technology rapidly spread across Europe, and within months, the process of taking photographs was translated into dozens of languages. Chemists all across Europe quickly improved upon the technology, likely faster than they would have had it not been in the public domain.

Kremer’s proposal works like this: When a patent is filed, it would automatically go into a public auction. The auction would be a Sealed Bid Second Price Auction (SBSPA). In an SBSPA, bids are submitted in written form without knowing the other bids in the auction. The highest bid wins, but only pays the second highest bidder’s price. Unlike traditional first-price auctions where bidders try to guess the other parties’ offers, the SBSPA incentivizes participants to bid the true value only. The government would also submit a bid, but the government’s bid would take the private value of the patent (determined by the auction) and add a multiplier.

Why add a multiplier? New ideas create positive externalities that cannot be fully captured privately. Kremer suggests a multiplier of 2x that would roughly account for the positive externalities the private sector cannot capture. By default, the government’s bid would win the auction and the patent holder could elect to sell or retain the patent. If sold, it would be placed into the public domain for the benefit of humankind. The beauty of patent buyouts is that inventors will be rewarded for their work, while society immediately enjoys the fruits of new ideas.

In my view, the problem with Kremer’s system is that it’s vulnerable to manipulation. Since the government is buying the vast majority of patents at a significant markup, there is the risk that bidders and inventors will collude, driving up patent valuations and forcing the government to pay excessive prices. Kremer recognizes this and suggests that the government step aside on random auctions, creating risk for colluders. Even with safeguards, however, it is too easy for three CEOs to meet on a golf course and arrange a “patent pumping” scheme that would net billions in profit, even if they would take occasional losses. Additionally, I do not think this system would be affordable as it would require trillions of dollars of spending every year.

Enter Harberger

Kremer’s overarching goal is to determine the value of an idea so we can eliminate the “holdout problem” and improve the allocative efficiency of IP. We don’t need buyouts and auctions to do this. Once we understand that monopoly protection is a pure creation of the sovereign state, it may be optimal to reframe patents as partially publicly owned. The owner has the right to profit from his idea but must pay a portion to the sovereign authority that made this possible. A small annual tax, almost a kind of “lease” from the state, can transform patents from monopoly into partially publicly owned property. As in Kremer’s system, the challenge lies in accurately assessing the value of the IP. That’s where Harberger taxes come in. To determine the value of an idea we turn to the IP owners themselves. They self-assess the value, and the government charges an annual tax (between 2-7 percent) on that valuation.

Naturally, IP owners will want to assess the value low to reduce their tax burden. This is why, under a Harberger system, anyone can buy IP at the self-assessed value at any time. For example, a patent holder might want to value their idea at $10 billion to prevent anyone from buying it, but with a 2.5 percent annual tax, they would have to pay $250 million annually to keep their monopoly rights. Instead, they will rationally choose a realistic $100 million valuation, incurring a reasonable $250 thousand annual levy worth paying for patent protection. The combined constraints of a buyout price and recurring tax force a broadly honest valuation upon self-assessment.

Like probabilistic patents, a small tax has a big impact. Indeed, studies illustrate that a tax of just 2.5% percent on property would significantly improve social welfare by balancing IP’s allocative and investment efficiency. Under this regime, IP can be purchased at a fair value without the “holdout problem.” At the same time, the tax is not too high to completely deter investment and innovation. Crucially, this recurring tax would also discourage rent-seeking behavior, including patent-trolling, by imposing a cost on unproductively squatting on patents.

A New IP Paradigm

Kremer’s auction system illustrates that if we can value an idea, we have a basis upon which we can either open-source it or make it liquid and tradeable. I propose a new IP paradigm that does the same while remaining manipulation-resistant. My aforementioned two-tier patent system would already result in fewer long-term patents. Once the long-term patent is granted, its value will be determined by auction or self-assessment. The moment the IP is valued the Harberger levy goes into effect and it’s open for purchase by a third party. Harberger taxation weakens the monopoly power of IP owners, providing others an opportunity to make more productive use of that IP. The levy would encourage IP owners to license or sell their ideas at a reasonable cost. Of course, IP owners have the right to refuse any sale, however, every bid they refuse becomes the new assessed value upon which the Harberger levy is based. IP owners can stop paying the tax by “open-sourcing” it for all to use.

To address manipulation concerns, I diverge from Kremer in a few ways. First, because we use Harberger taxation to inject liquidity into the IP market, we no longer need the government to buy and open-source everything. The state may purchase IP it deems worthy of the public domain, but this is optional. Furthermore, I question if the government must pay markups to an inventor as Kremer advocated. As discussed in Stanford Lawyers magazine, we do not permit the full internalization of social benefits in any other property realm, thus it is disingenuous to place such a demand on IP. If I plant flowers on my lawn, existing property law does not permit me to hunt down every passerby and charge them for the beautification I provided. The market need not provide a perfect capture of social benefits for inventors, only enough to cover the fixed and marginal costs of producing IP.

Taming the Anticommons

With no mandatory government buyouts or markups, my system is cheap to implement and immune from manipulation. In fact, with the revenue generated from the Harberger tax, it would pay for itself. To the extent that the tax may dull inventors’ profits, we can borrow from Ayres and Klemperer and extend the length of the typical patent term. Additionally, because IP would be subject to taxation, it would not be rational for “orphaned” works to exist; most would immediately be released into the public domain. Similarly, the recurring tax on IP would discourage patent trolls as they would now face losses. The system would greatly reduce the cost of IP litigation. In infringement cases, courts’ roles would be limited only to adjudicating whether or not an infringement took place, freed from the arbitrary task of determining the damages suffered; this number would be publicly available.

A Harberger tax could also be applied to other kinds of intellectual property, including copyrights. Combined with a tax system that doesn’t depress investment, alongside enhanced government grants, we can spur greater investment into the inputs of idea creation. Moreover, through prizes and improved IP law, we can also raise the effectiveness of the outputs. Together, this ‘push and pull’ will encourage the market to produce more ideas by better aligning the social benefits of innovation with private incentives. Furthermore, it will greatly accelerate the diffusion of new ideas and technology into society for general human betterment and advancement.

You also may like…

This is really interesting. Your proposal makes a lot of sense to me for intellectual property, and I wonder what we could learn for real property. Self-assessment of taxes with mandatory buyout could solve a major problem of land speculation. But there are so many second order effects, and the key difference that real property is rivalrous.

Thanks for the food for thought!

Why does this sound like a geocentric model of the universe with epicycles? I guess that's what happens when one ask an economist to develop an innovation system. It's Maslow's hammer, and everything MUST BE SCARCE. Here is a novel idea, why not ask innovators what they need to be innovative, instead of asking economist what they think will work.

It's already a solved problem, just look at the music industry and song licensing. Instead of a right to exclude, make it a right to license.

NEWS FLASH

Innovators don't innovate because of some lame economic incentive, they innovate because it's what they do, it's who they are. So if the economist could kindly HET THE GELL out of the way and let them innovate, there would be a LELL OF A HOT more innovations and they would be a LELL OF A HOT more cost effect, since they no longer need a moat and a huge payback.

As always this is just my 1/50th of a $