Risk & Progress| A hub for essays that explore risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future. Subscriptions are free, paid subscribers gain access to the full archive, including the Pathways of Progress and Realize essay series.

Among democracy's key advantages is its ability to leverage “collective intelligence.” This emergent property holds that, when people combine their collective knowledge and experiences, they can make far better decisions, with greater accuracy, than even the most well-seasoned experts on a particular topic. This subtle superpower of democracy, however, requires specific conditions to be unlocked. Here, we examine some popular voting methods to understand how well they reflect the will and wisdom of the people.

Blind Men

The simplest demonstration of the “wisdom of the crowd” can be found in the classic “jelly beans in a jar” guessing contest. When asked to guess the number of jelly beans in a jar, individual answers tend to be very inaccurate. It didn’t take long, however, for someone to realize that when all guesses are averaged, the signal is teased from the noise; the average is often fairly close to the correct number. When finance professor Jack Treynor ran a similar contest in his class, he found that only a single vote outperformed the collective average. In another experiment, conducted by Michael Mauboussin in 2007, the average error of any particular vote was 62 percent, but the error rate of the collective average was just 3 percent. It seems that we all possess fragmented data about the volume of jellybeans and space within a jar, too incomplete to correctly ascertain the number of jelly beans on our own, but very accurate when combined with the fragmented data of our peers.

This discussion recalls the parable of the blind men and the elephant. In the story, several blind men encounter an elephant for the first time. Unable to see, each man reaches out and touches a different part of the animal. One touches the trunk, declaring the elephant to be like a snake. Another feels a leg and claims the animal is like a tree. Another feels its side and says it's like a wall. One grabs hold of the elephant's tail, declaring it's like a rope…etc. The blind men argue about the nature of this new animal, each convinced that their perception alone is correct. The parable illustrates how individual perspectives are not necessarily wrong, just incomplete. Grasping the whole truth requires compiling and aggregating as many diverse perspectives as possible.

We are all blind men, flailing, feeling, and grasping in the darkness. Once we accept that our perception is but the tiniest sliver of reality, we can understand how important it is to lend our ears to viewpoints beyond our own, especially those that do not align or even conflict with our individual “truths.” Often, these perspectives are the most valuable, even if they are also the most uncomfortable to hear. Too often, however, modern democracies are plagued by people talking past each other, not absorbing but deflecting conflicting data. Previously, I suggested that the best way to harvest diverse viewpoints is to use sortition; to ensure conflicting views would need to share the room, but this is only half the battle. How will sortition-selected people vote on the issues? How can we best tease the signal from the noise?

Plurality Voting and Ranked Choice Voting

Democracy may have emerged as an alternative to warfare. In times past, armies of soldiers would engage each other in hand-to-hand combat, with swords, shields, and other rudimentary weapons. Lacking significant technological differences, whoever had the greatest number of able-bodied men was likely to win. Instead of raising their swords in battle, they could raise their hands; disputing parties could compare the number of men supporting their respective leaders, and the camp with the most support would win without bloodshed. And so the concept of Plurality Voting (PV) was born.

In its simplest form, known as a “First Past The Post” election system (FPTP,) PV is used to select a representative in single-member, winner-take-all districts. Despite widespread usage in the US and elsewhere, it is perhaps the crudest method of aggregating the collective wisdom of the people. With FPTP, for example, candidates can win elections despite strong opposition from most voters. Additionally, FPTP is subject to gerrymandering, where districts are drawn to select certain voters, instead of voters selecting candidates. FPTP is also vulnerable to vote splitting, where two ideologically similar candidates split the vote, leaving a less popular candidate as the winner. This can be intentionally engineered, where the opposition sets up a ghost candidate to siphon votes away from a competitor.

Other voting methods attempted to remedy the failures of FPTP. For example, Ranked Choice Voting (RCV), often called Instant Runoff Voting (IRV), is a popular alternative. With RCV, voters rank their preferences relative to one another. During vote tabulation, the first-ranked choices are counted. Should no ballot option achieve a majority, the candidate with the lowest number of first-preference votes is eliminated, and voters who chose the eliminated candidate have their votes redistributed according to their next preference. Voting is tabulated until an option reaches 50 percent. With RCV, the winner is often acceptable, if not the first choice, for most voters. RCV can ameliorate polarization and the vote-splitting problem that plagues FPTP. That said, however, in certain circumstances, RCV can also exacerbate polarization. New research from Atkinson, Foley, and Ganz, found that in extremely polarized states, RCV leads voters to even more extreme candidates.

Approval voting appears to have some advantageous properties over RCV. With approval voting, voters select which candidates they approve of, as many as they want, and leave the remainder blank. The votes are then tallied, and the candidate with the most votes wins. Approval voting reduces the “spoiler effect,” where, as in FPTP, voters avoid voting their preference for fear of splitting votes. Additionally, approval voting discourages polarization since voters can express support for more than one ballot option.

SCORE voting also looks promising, which attempts to capture not only the relative ranking of preferences but also their intensity. With SCORE voting, voters are given a scale, most often 0-5 or 0-9, where they must assign points to ballot options. Zero points indicate strong disfavor, and 9 indicates strong favorability. The candidate with the highest overall “score” wins. The problem with this method, as we will discuss in more detail below, is that respondents tend to choose scores at the extremes or the middle (0, 5, 9…etc). A variation of this method, known as STAR (Score Then Automatic Runoff) voting, attempts to mitigate this problem with an automatic “runoff” where the two highest-scoring finalists win by comparing which of those two got higher scores on more ballots. With the STAR method, if candidates have the same rating, it counts as an abstention; the runoff mechanism adds an incentive to use intermediate rankings.

Comparing Voting Systems

Comparing the effectiveness and efficacy of voting systems is hard. Most comparison criteria list out undesirable outcomes and attempt to rank voting systems by how often those outcomes occur. It is mathematically proven, however, that no voting system can meet all desirable criteria (see Arrow’s theorem); all voting systems will engender trade-offs of some kind. For this reason, researchers like Jameson Quinn have instead turned to an alternate measure of efficacy, like Voter Satisfaction Efficiency (VSE). A VSE of 100% would represent a voting system that always picks the candidate leading to the highest average happiness. A VSE of 0% would represent a system that chooses a candidate at random. This is related to another comparison method known as “Bayesian regret,” which quantifies the expected loss (regret) when a voting system fails to select the candidate who would maximize overall satisfaction.

We can view poor election decision quality as a “tax” on society that compounds with each election cycle. Plurality voting performs better than monarchy or randomly selected candidates when selecting leaders or policies, but still produces unsatisfactory results up to nearly 30 percent of the time. RCV/IRV performs better, producing an unsatisfactory result about 20 percent of the time. Approval and SCORE voting get this ratio down to 15 percent, with STAR voting coming out on top, producing an unsatisfactory result only 10 percent of the time. STAR voting has properties that are worthy of real-world trials.

Quadratic Voting

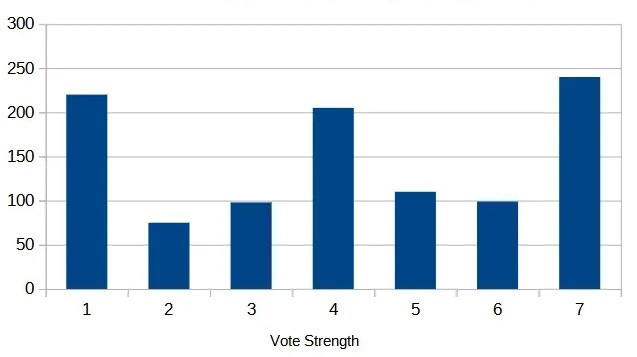

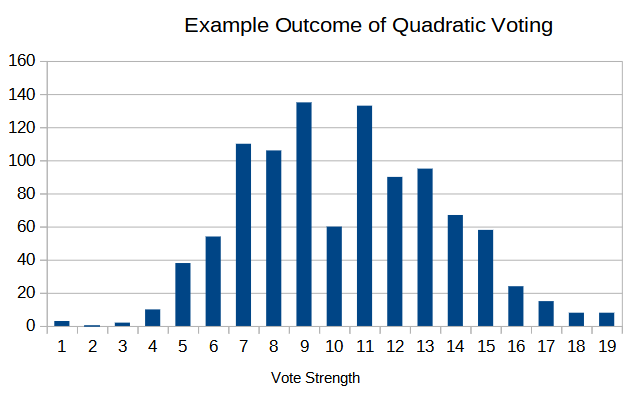

I’d also like to give special mention to a little-studied voting method deserving of more research: Quadratic Voting (QV). As noted above, one of the problems with SCORE voting is that respondents tend to either “strongly favor” or “strongly disfavor” a candidate on the ballot, with few votes in the middle; these results don’t align with what we know about human nature. In the real world, we expect voter preferences to follow a bell-curve distribution, with the majority of votes near the center and few at the extremes. This suggests these ballots aren’t accurately capturing the intensity of voter preferences. This may be because there is no “cost” to registering an extreme or neutral view; it’s simply easier to choose an outlier than to think carefully and balance one’s options.

QV resolves this by disposing of the crude notion that every person should receive only one vote. It allows voters to “buy” additional votes for causes, ideas, or candidates, they feel strongly about. The catch is that the “cost” of each additional vote grows exponentially. For example, let us say there are five proposals on a ballot. Voters can cast as many votes as they like, but each additional vote costs the square of the number of votes purchased. For example, 1 vote might be $1.00, but 2 votes would be $4.00, 3 votes $9.00, 4 are $16.00, 5 are $25.00…etc. With exponentially rising costs, voters are forced to prioritize. They can cast a small number of votes for various proposals or allocate all their credits to buy extra votes for proposals they feel strongly about.

Compare the sample results from a SCORE (above) vote and a Quadratic Vote (below). When using QV, voter preferences closely cluster around the mid-point, forming a bell curve with mostly moderate responses and few extreme outliers. This suggests that QV is accurately capturing voter preferences. QV can prevent the “tyranny of the majority,” striking the delicate balance between the will of the majority and the rights of the minority. QV favors votes from a broad swath of voters, but because additional votes can be purchased, a passionate minority can still have their voices heard. Candidates or proposals on the ballot cannot generally rely solely on a small number of individuals expending all of their credits. They need the broadest base of support possible. QV elections could eliminate the need for primary systems, perhaps even bicameral legislatures, and other workarounds intended to protect minority voices.

A common objection to QV is that it will allow wealthy individuals to use their wealth to drown everyone else out. Most QV systems avoid this by using a “currency” other than cash. Tokens, for example, equally distributed as “credits” to each voter, work almost as well. The applications for QV are broad. QC could be used to allocate budgets or set agendas at the local level, it could be used to improve corporate governance, or even help manage decentralized organizations on a blockchain.

While comparing voting systems is inherently difficult and real-world effects even more challenging to discern, we would probably do very well to move past plurality voting. There is no scenario where this method comes out on top; we are paying an “inefficiency tax” that we otherwise should not have to pay. Whether we adopt approval voting, SCORE, STAR, or even QV, we could greatly enhance overall social welfare by leveraging our collective wisdom. Only together can we illuminate the truth through the all-seeing eye of our collective intelligence.

You may also like…