Risk & Progress| A hub for essays that explore risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future. Subscriptions are free, paid subscribers gain access to the full archive, including the Pathways of Progress and Realize essay series.

Scale matters, especially when we are talking about human progress. In his aptly named book, Scale, physicist Geoffrey West describes scaling laws that underlie everything from individual organisms and corporations to the very cities that we live in. Scaling laws kicked progress into overdrive as technology freed humans from the farms to move into cities. There, the same cognitive hardware that drew pictures on cave walls, invented flying machines, microchips, and space-faring vehicles. Overzealous zoning regulations, however, threaten to stifle us in the 21st century. The time has come to let the skyscrapers bloom.

We have already witnessed how the square-cube law dictated the maximum size of early single-celled organisms and why this forced life to become multicellular, but scaling effects are everywhere. Kleiber’s Law, for example, holds that as organisms double in size, their metabolic rate increases by only 75%, not double as logic would normally have. Metabolic rates, in other words, grow sublinearly to body mass, in what may be thought of as a kind of “economies of scale” in biology. Similar scaling patterns have been found between life spans and heartbeats. All mammals appear to live for an average of 1.5 billion heartbeats.

Lifespans, therefore, are largely dictated by how fast a mammal’s heart beats. A shrew’s heart, for example, can beat 1000 times a minute, thus limiting them to a 2-3 year life. Humans are the exception, living for an average of 2.5 billion beats. It wasn’t always this way, however, we too were bound by our biological limitations until the Second Industrial Revolution. It took immense technological advances, which saw a rapid drop in infant mortality and a corresponding increase in life expectancies, to break free of mammalian limitations. Progress, in other words, can literally bend the laws of nature. But it can also work the other way around, scaling laws can give rise to progress itself.

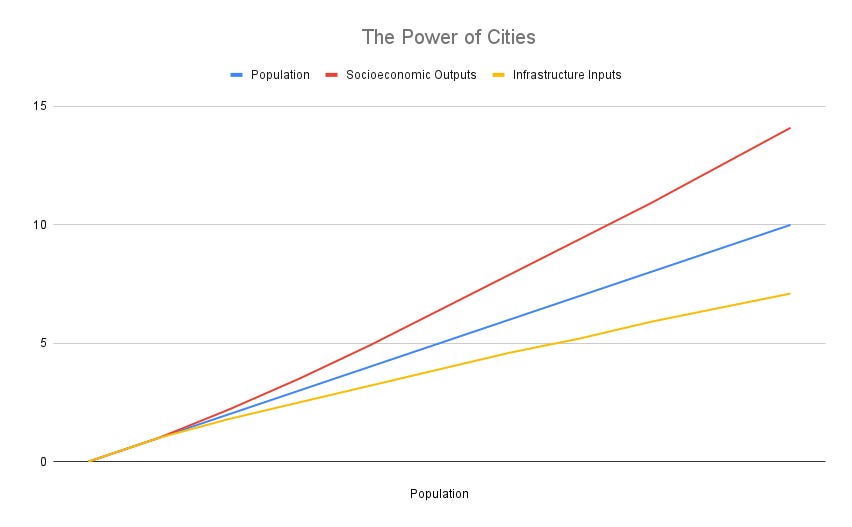

As I noted earlier in our discussion of the “social supercomputer,” human cities also obey predictable scaling laws. To reiterate, two exponents tend to reign supreme, 0.85 and 1.15. Infrastructure as measured by the length of roads, piping, electric lines, fiber optic cables, or even the number of gas stations in a city, scales sublinearly with population size to the exponent of 0.85. This means the population grows faster than the total infrastructure required to support it. On the other hand, socioeconomic output, such as the number of patents produced, GDP, and even average incomes for its inhabitants, scale superlinearly to the exponent of 1.15. The more people a city has, the more innovative and wealthier it will tend to be. Dense cities make better use of our economic, technological, and human capital. Thus, limiting city size and density also limits the frontiers of human destiny.

Housing Crisis

Earlier I discussed the negative effects of high housing costs, which run broad and deep. The cause, as many have identified, is a mismatch between the supply of available housing and the demand for it. I fingered Euclidean zoning as the primary cause of this misalignment, which restricts land to exclusive uses, often either residential, industrial, or commercial. Further, zoning rules tend to limit the density of housing allowed on residentially zoned tracts. Short of abandoning zoning laws altogether, is it possible to develop reasonable regulations that balance urban habitability with demand? I think the answer is yes.

As a general rule of thumb, the goal should be to restrain the median housing price in a particular jurisdiction to about three times the median household income within the same area. In 1969, almost every metropolitan district in the United States had a median cost-to-income ratio under 3.0 and the average was just 1.8! This is no longer true today as zoning rules became progressively more restrictive after the 1960s. If we can design a zoning policy that can react more flexibly with demand, the cost of housing would gradually converge closer to the base construction cost.

One alternative to Euclidean zoning that has been gaining traction since the 1990s is “Form-Based Codes” or FBC. Like Euclidean Zoning, FBC attempts to prevent the negative externalities of industrialization and make our cities more livable. It does so, however, in a more flexible fashion. FBC de-emphasizes the use of land, focusing instead on the physical form of the structure built upon the land and its interaction with the surrounding city. FBC-based neighborhoods are more attractive, more inviting, and walkable than those based on Euclidean zoning. More importantly, because they do not restrict housing density nor mandate a single exclusive use, it’s possible to build apartments/condos with convenient businesses and shops on the ground level. While not a perfect solution, Form-Based Codes offer an attractive alternative to the current zoning approach used in North America.

Another alternative model can be found in Japan, where uniquely, zoning laws are standardized at the national level with cities and local governments’ power limited to rule implementation. This is crucial because it limits the ability of zoning boards and local governments to design the rules to inflate their own property prices. As I have noted, this kind of mini-regulatory capture is not socially, economically, or morally optimal. In Japan, there are only 12 zone types, greatly simplifying administration compared to the hundreds of variants and subvariants of zones found in the United States and other countries. The Japanese order these zones in terms of maximum potential “nuisance,” and like FBC, Japanese zones are not limited to a single exclusive use. The zones might be thought of as “inclusive” rather than “exclusive.” See the chart below that illustrates the difference:

Within these zones, buildings’ shape is determined by the maximum or minimum floor-to-area ratio and height. Height restrictions are also put in place to ensure proper sunlight and ventilation, but unlike North American height restrictions that tend to be absolute and arbitrary, Japanese zoning is flexible. Instead, the maximum allowable height is determined by a formula that accounts for the setback from the road and road width. There is no reason, for example, to impose a two-story height limit on a building that is set back 50 meters from everything else.

Further, residential zones do not differentiate between residence types. Residential is residential, whether that may be a single-family home, duplex, or condominium. All residential building types can coexist within the same zone, allowing the housing supply to adjust to demand in that area. Consumers are more likely to find a home that fits their needs and price point, rather than having to shoehorn themselves into the existing housing stock. As a consequence of Japan’s flexible zoning regime, cities like Tokyo have remained relatively affordable compared to other major metropolitan areas, even as the population grew extremely large.

Tax the Land

We should not stop there. Ideally, the adoption of flexible zoning would be paired with an effort to replace property taxes with a Land Value Tax (LVT). As we will soon see, an LVT levies tax on the unimproved rental value of land, instead of the property built upon it. By taxing only the land, we could discourage wasteful land speculation and simultaneously eliminate the de-facto “punishment” that accompanies development. With LVT, land use would be allocated much more efficiently, and land prices would fall dramatically. Parking lots, vacant lots, and other suboptimal land uses would be replaced with housing, offices, and shops. Together, flexible zoning and affordable land would bring the housing crisis to an end and greatly accelerate economic growth. Cities, our crucibles of innovation, would burn hotter, churning out more opportunities than ever before.

You also may like…

A great article. I really enjoyed reading it, especially the first part about the scaling laws. That's something new that I have learned.

It also has good suggestions for policies. What specifically we should do to stimulate more optimal and innovative growth.

I love your ideas and your grasp of policy. But what is the pathway to implement these ideas? How do you defeat the elderly NIMBYs who have already captured the regulatory apparatus?