Risk & Progress| A hub for essays that explore risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future. Subscriptions are free, paid subscribers gain access to the full archive, including the Pathways of Progress and Realize essay series.

As we will discuss, media and popular culture are inherently biased to highlight the negatives of modern life. Basking in such negativity, it’s not always easy to accept that, as of 2025, we are privileged to live in the best time in human history. Yet, even this very suggestion often triggers immediate scorn and disbelief, a reflex that is understandable and difficult to break. To truly understand the depth and impact of human progress in these past few centuries, we best turn to charts, graphics, and data. Only with our eyes can we visualize the whirlwind of positive change that has enabled unparalleled human prosperity and personal opportunity.

Education

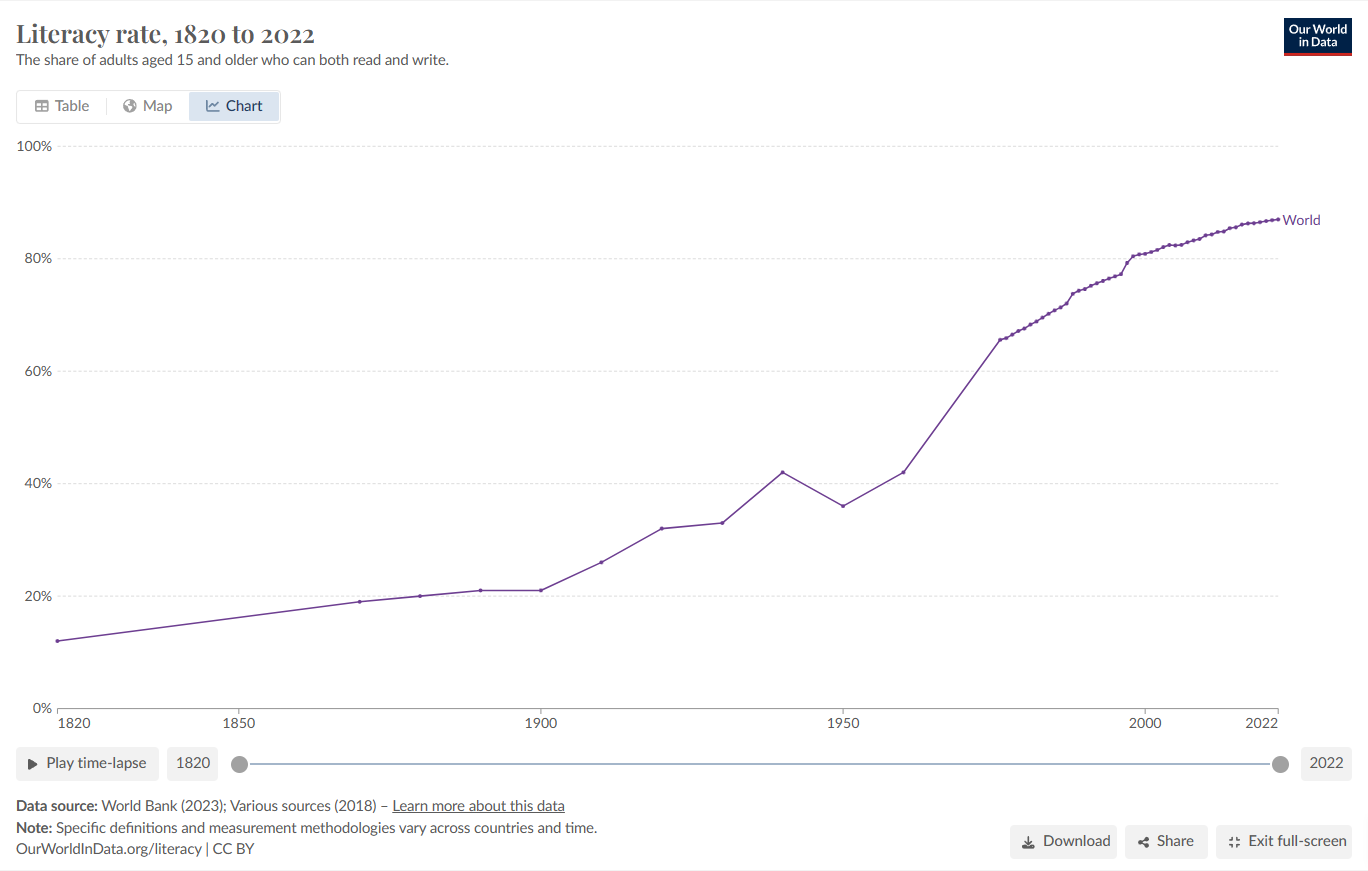

Let’s begin with literacy, as it is a key metric of human progress and individual potential. The ability to read and write unlocks the capability of learning from others through books and written works, and the accelerated dispersion of knowledge. Literacy was once a privilege reserved for an elite few. Yet, since the industrial era, we can see a literal inversion in illiteracy. Global literacy soared over the last two centuries, inverting the proportion of people who are literate and illiterate. In other words, humanity progressed from 12 percent literate in 1820 to 12 percent illiterate in 2020.

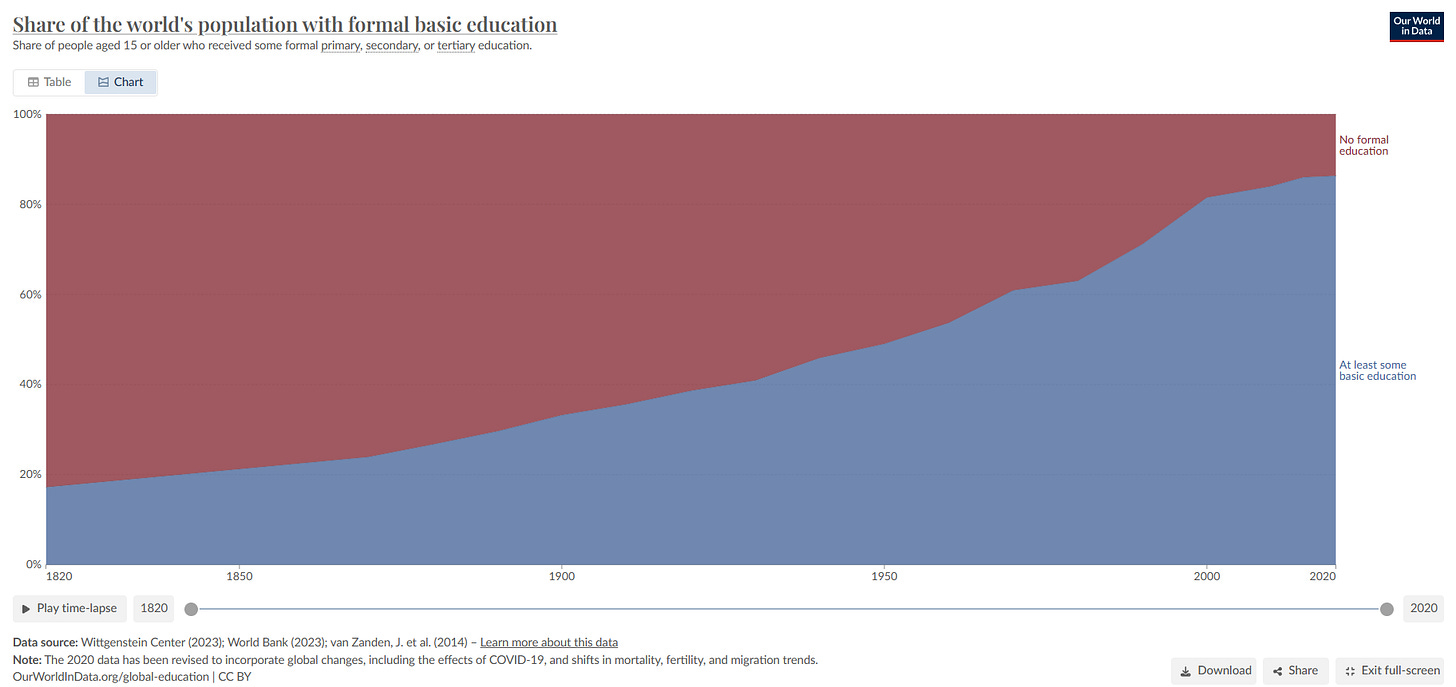

Perhaps unsurprisingly, literacy rose as basic education became more prevalent. This, too, began in earnest after the Industrial Revolution. In 1820, just 17 percent of children under the age of 15 had received any formal education. By 2020, over 86 percent could say the same.

Health

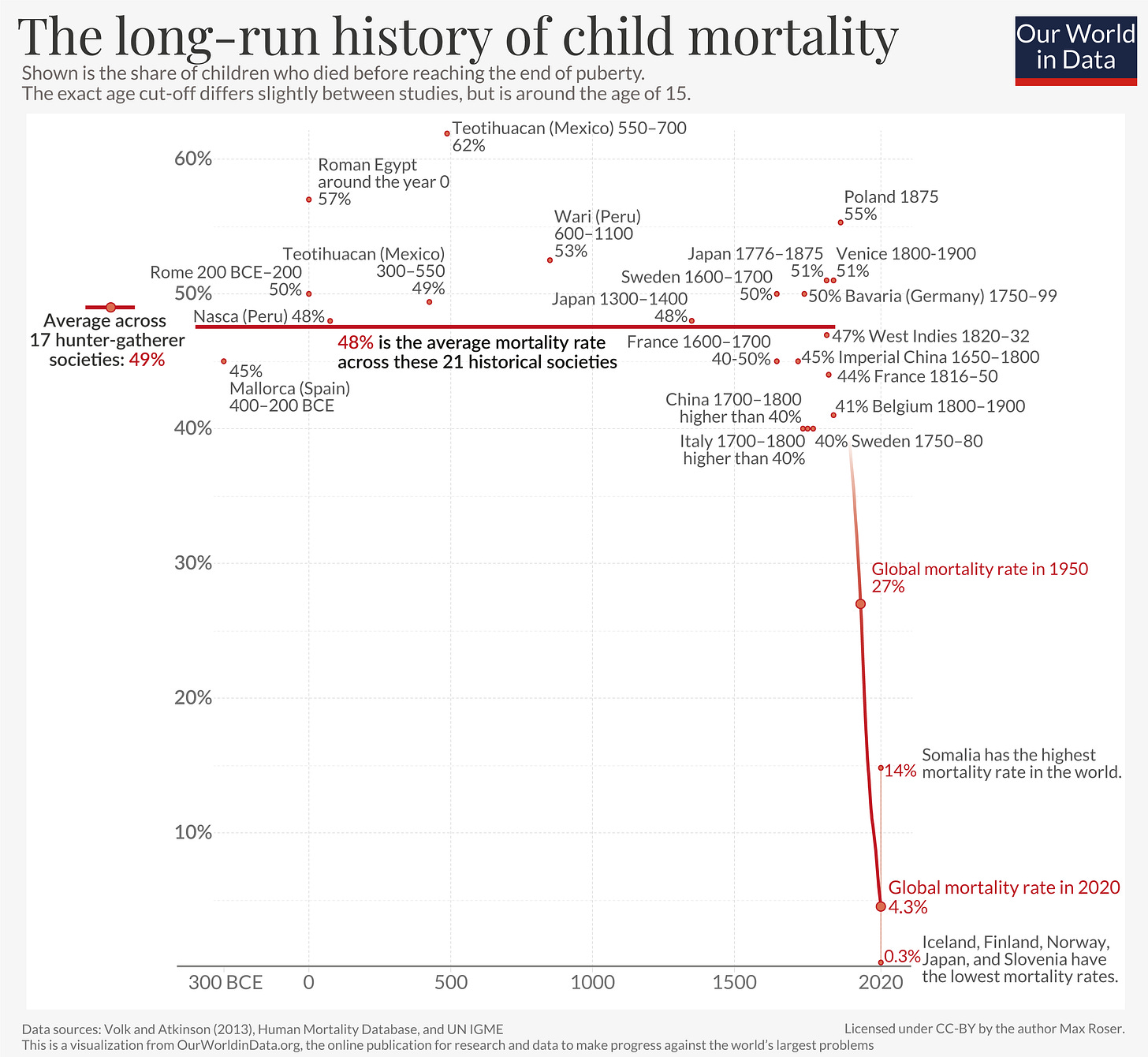

For most of human history, having a child was like rolling the dice. Parents faced a roughly 50 percent chance of losing each child before age 15. Since the Industrial Revolution, this risk has plummeted. Thanks to new technologies and better hygiene, global child mortality is now around 4 percent, and even lower in wealthy, developed countries.

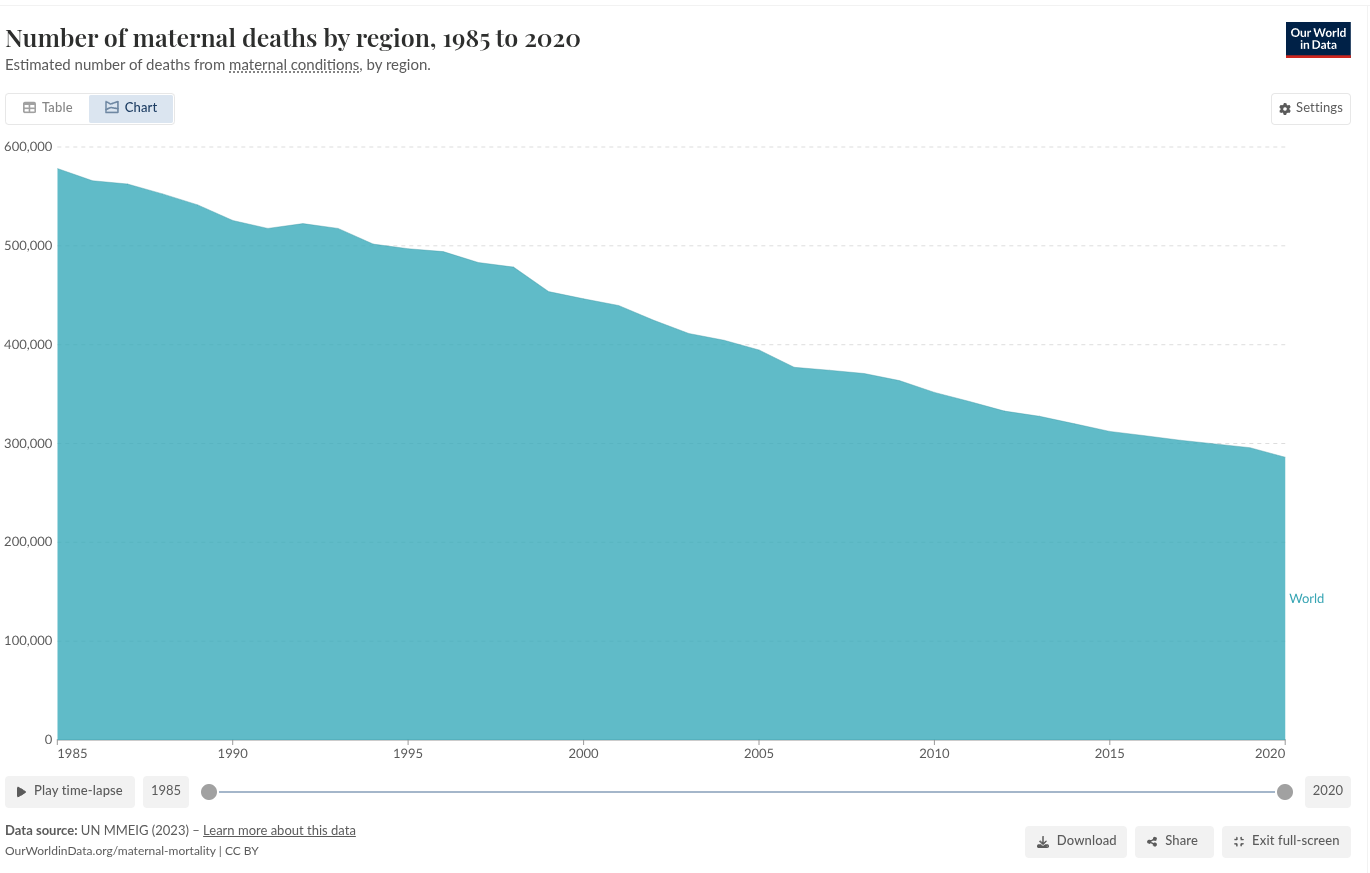

Maternal mortality, which measures the ratio of women who die within 42 days of giving birth (measured per 100,000 live births), has also been cut in half globally since 1985, when the first data became available.

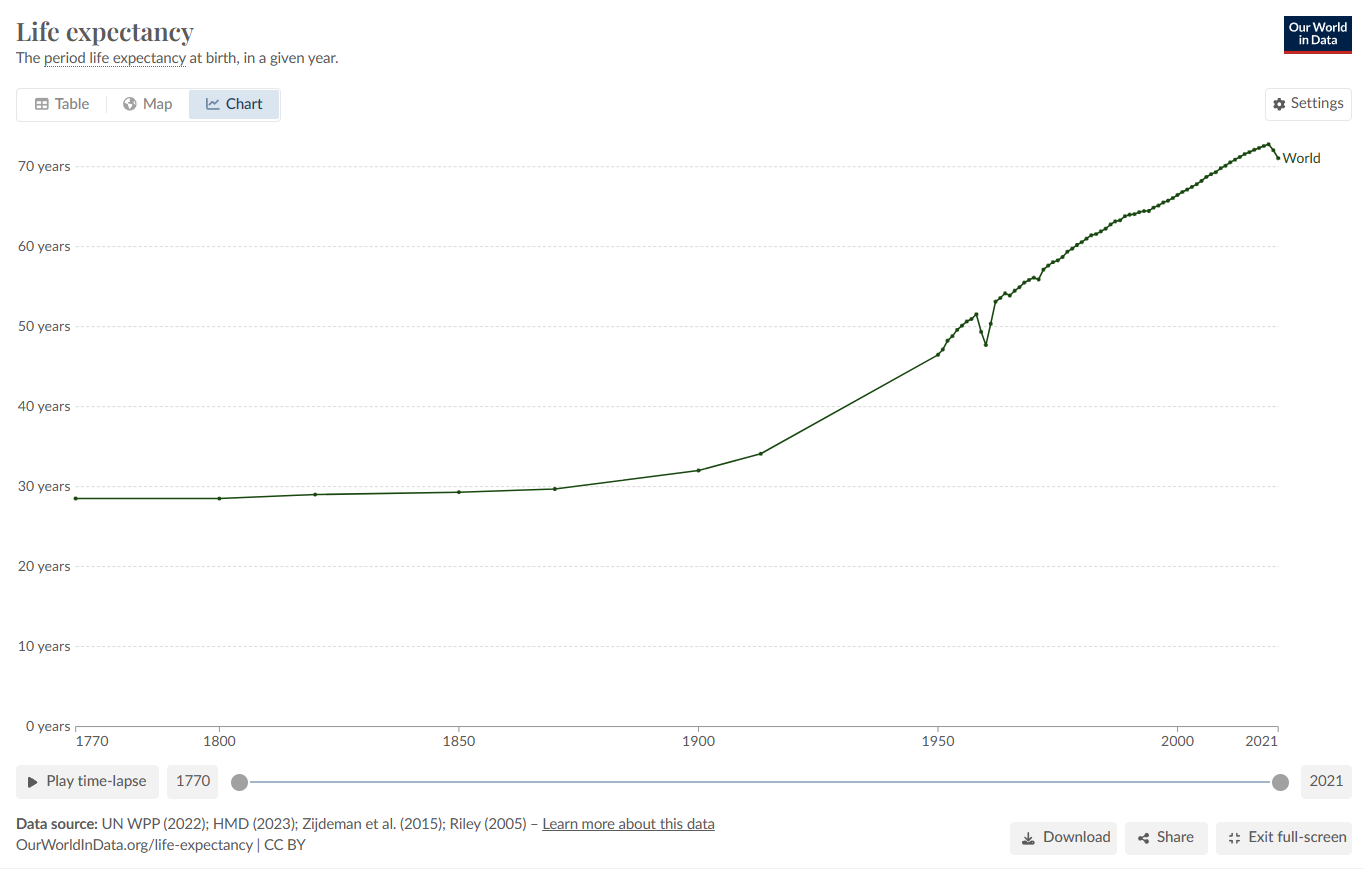

Since the Industrial Revolution, more of us can enjoy life. At the same time, incredible advances in medical technology have also allowed us to live much longer. Globally, the average life expectancy has risen dramatically from 29 years in 1820 to 72 years in 2020. In many wealthy nations, the average life expectancy is now over 80 years.

Wealth

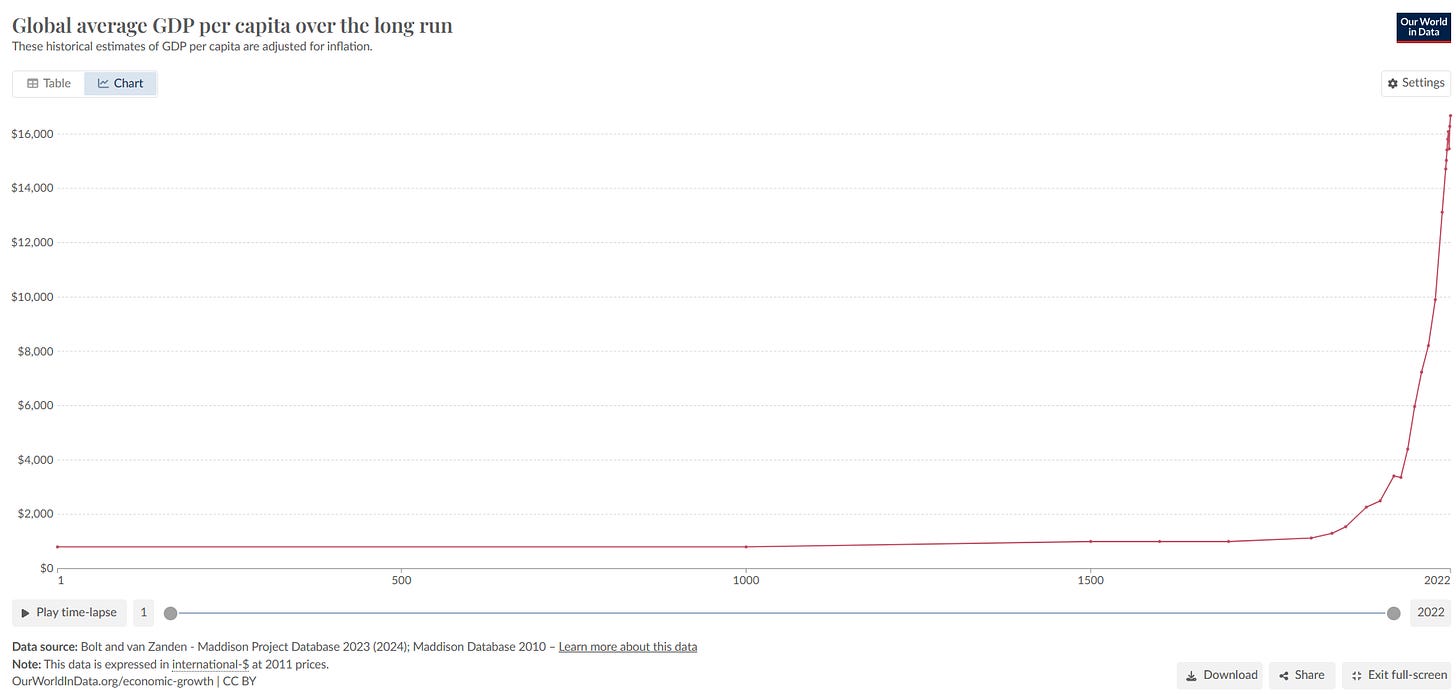

Material “wealth” is understandably controversial, but as we will discuss, wealth is merely another key performance indicator of human progress and the expansion of our knowledge base. Wealth brings us opportunity and individual capability. For most of our history, the vast majority of humanity was extremely poor, grinding away a subsistence existence, with just enough food to live and reproduce. Our “wealth” grew very slowly, beginning with the agricultural revolution, before again exploding during the Industrial Revolution after 1800.

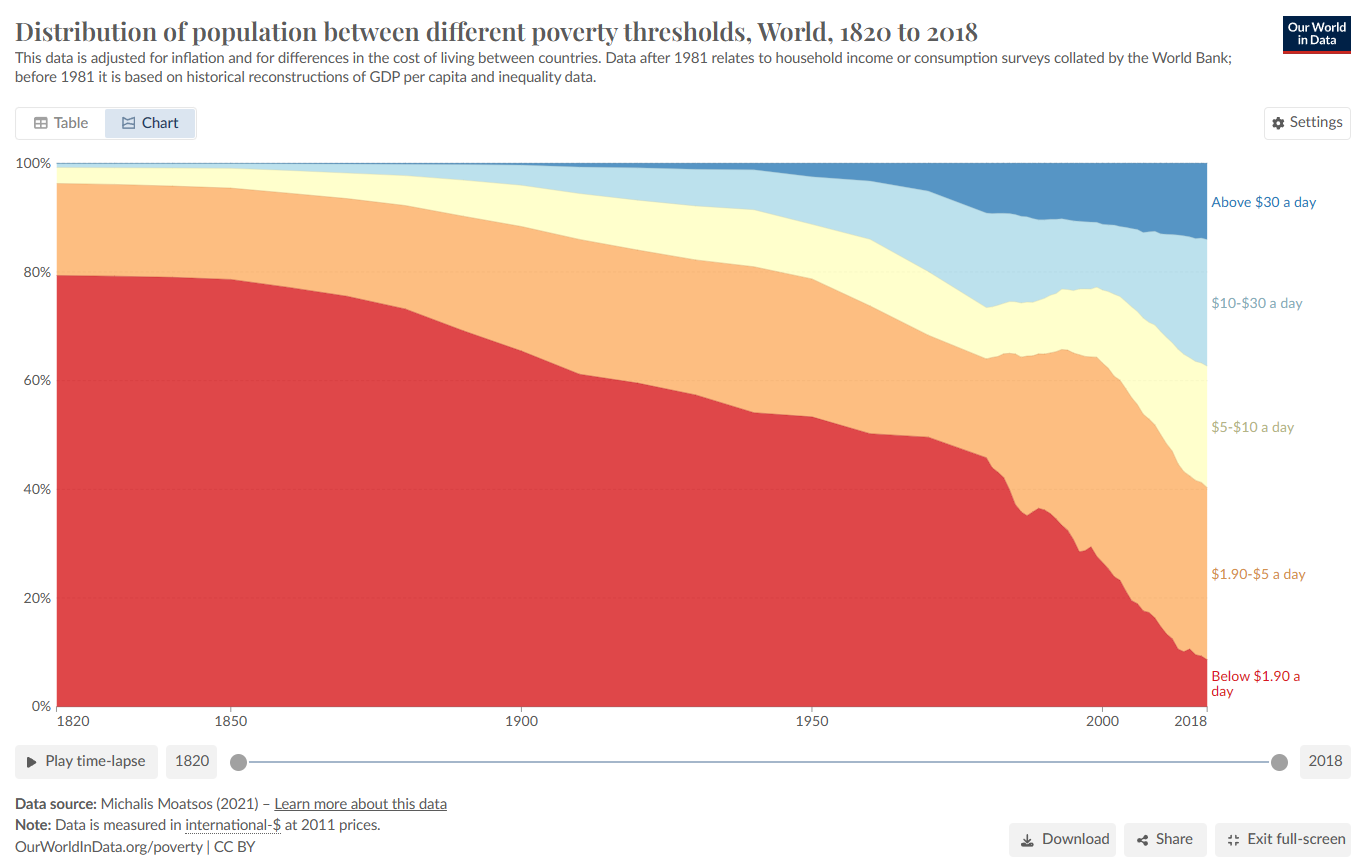

It’s common to assume that this wealth only benefited the “rich.” The data, however, paints a much more complex story that we will also explore. Even the poorest among us are benefiting from economic growth; the percentage of people living in extreme poverty has fallen. The collapse is most pronounced after about 1980, with the rise of globalization and the global marketplace.

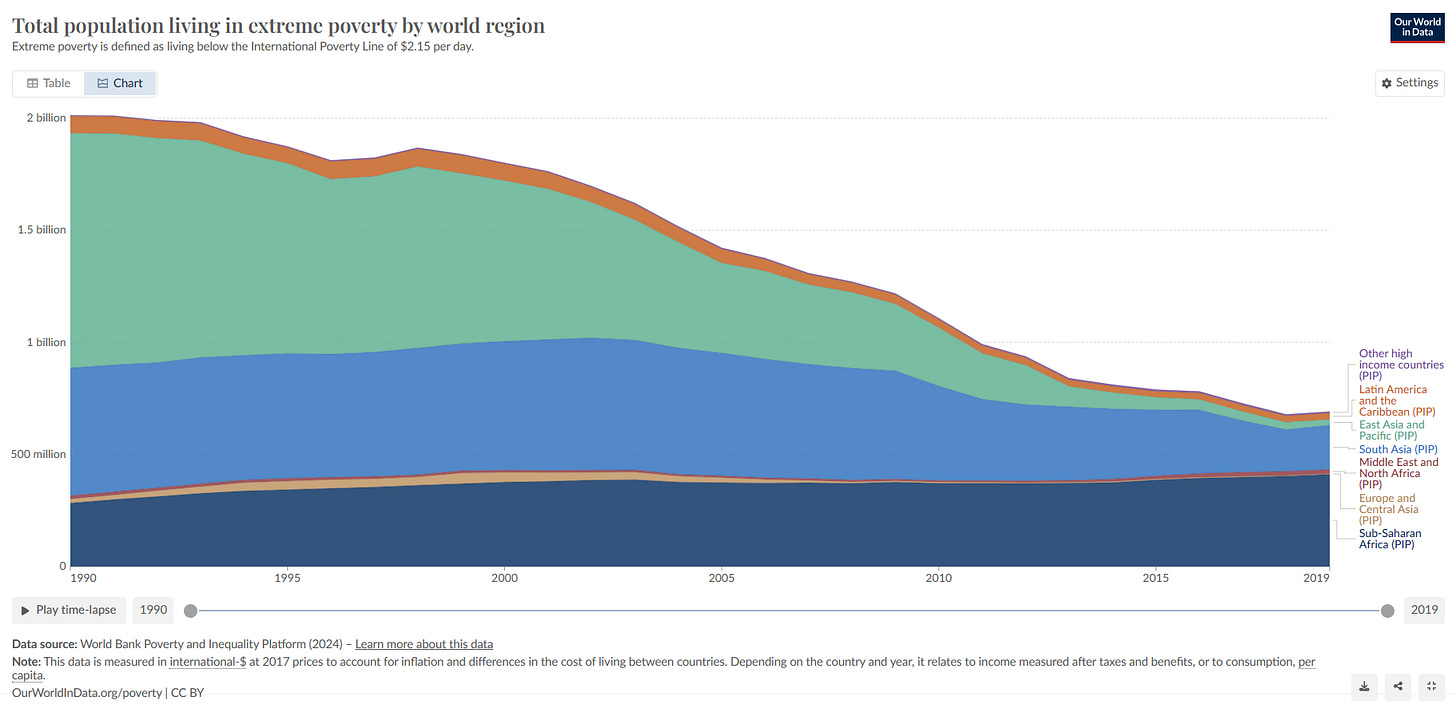

It’s not just the percentages that shrank either. The total number of people living in absolute poverty has shrunk as well from about 2 billion in 1990 to under 700 million in 2019. This is remarkable, even if much work remains to be done.

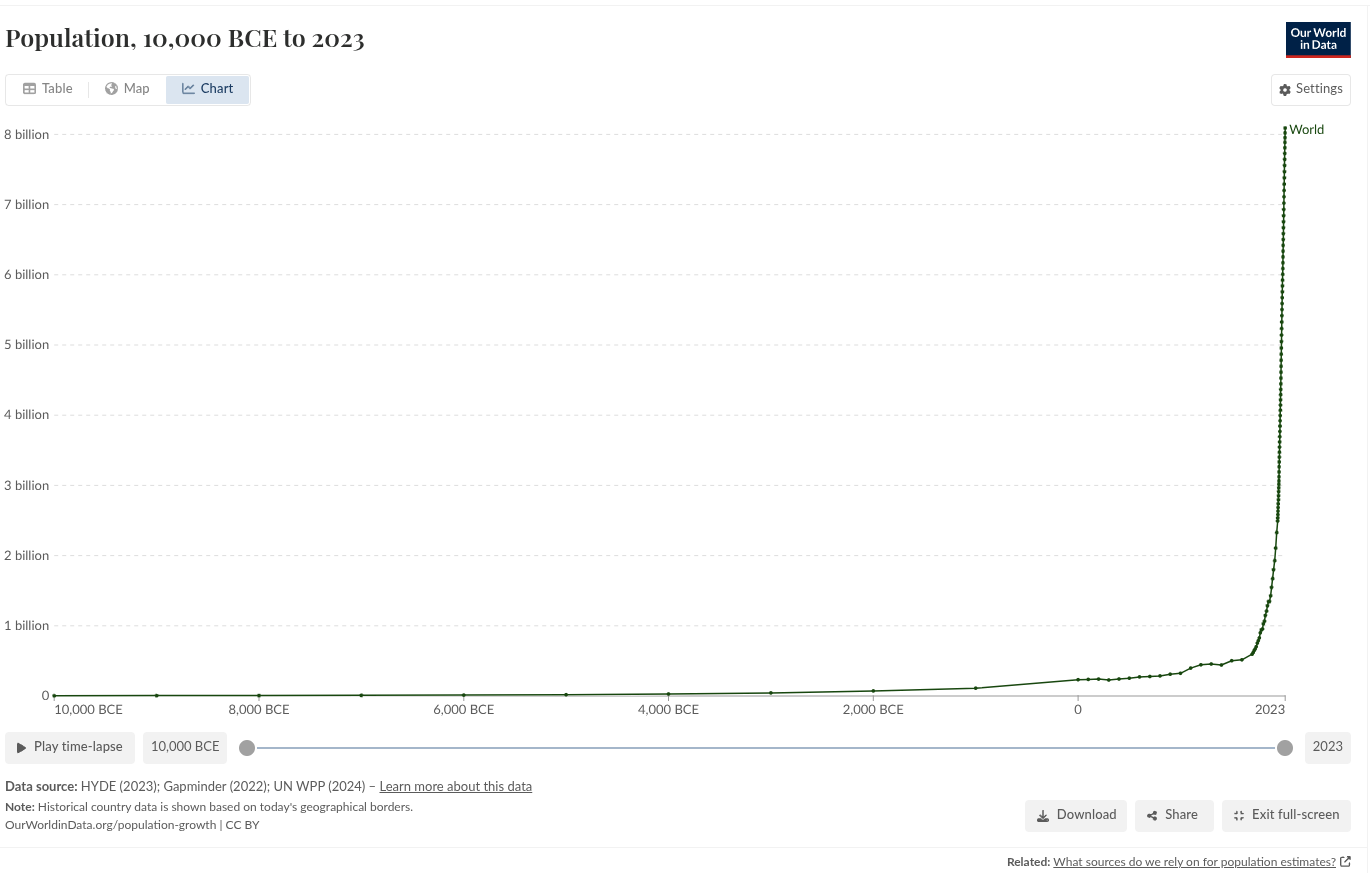

Paradoxically, this also happened while the total number of humans on this planet exploded. Indeed, I will make the case that poverty shrank because, not despite, our growing numbers. We can see our population begin to rise with the agricultural revolution, but again, fail to truly “take off” until the Industrial Revolution.

A Better World

Today, most of us live lives of relative luxury compared with our ancestors. Our environments are safer, we can expect to live longer, more comfortably, and with access to vastly greater material wealth. We also have more opportunities to create, build, explore, and yes, destroy. In my view, progress is never finished, and much work remains to be done. The goal of Pathways of Progress is to understand how we cultivated progress in the first place, what set off that “spark,” that “explosion,” we see in the charts above, and how we can sustain and spread the fruits of human advancement to more people around the world.

You also may like…

I remember when Pinker's book Enlightenment Now came out with example after example like this, the main critizism is that it doesn't 'feel' like that to many people and telling them otherwise undermines their 'lived expereince.'

I worked with a woman who was extremely worried about violence on women in 2020 and compared that to her own expereince as a college kid touring India solo in the 90s when she felt it was safer. When I pulled up the numbers and showed her that she was SIGNIFICANTLY more at risk back then, I got HR called on me for the crime of minimizing violence on women. I told HR that I didn't justify it, I contextualized it. That wasn't good enough. Because violence still existed and because this women felt it was worse, my sharing that it was orders of magnitude safer was offensive.

I think few will doubt that a number of challenges have been solved, and in a narrow sense progress is irrefutable. On average people do live longer, are healthier, and have basic literacy. I wonder though, if not a comparable model is the life of many animals in captivity. They too live longer and healthier. If captivity is progress for them, it would seem a rather hollow victory, and more importantly, it challenges the assumption that raising these basic metrics is a good proxy for meaningful progress (whatever that may be).