Risk & Progress| A hub for essays that explore risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future. Subscriptions are free, paid subscribers gain access to the full archive, including the Pathways of Progress and Realize essay series.

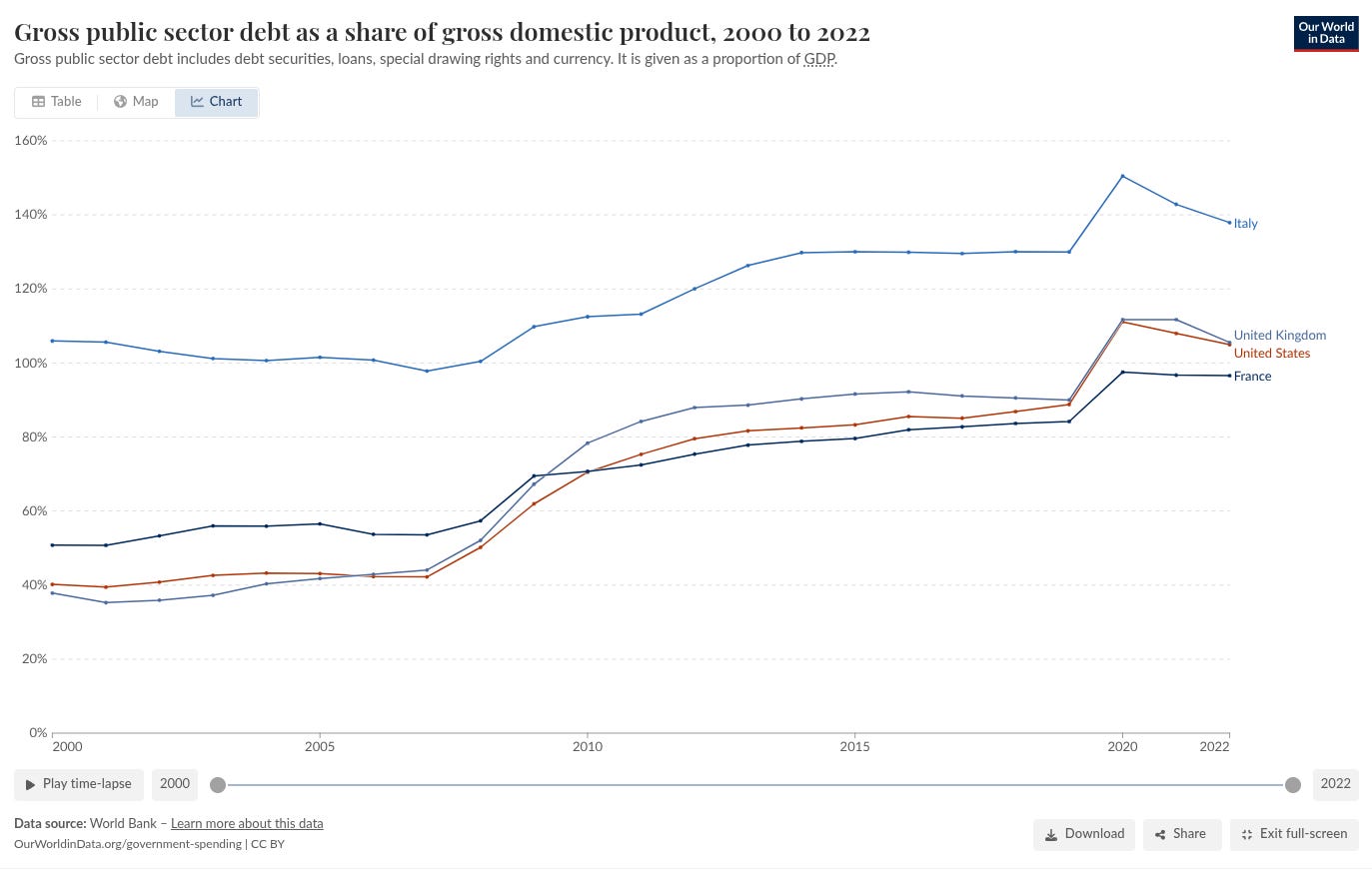

The United States owes over $36 trillion to creditors, and many developed nations carry similar unsustainable debt loads. Much of this debt arises from financing entitlement commitments that citizens have come to expect and depend on. While cost disease and supply constraints have worked to drive up the cost of many public services, suboptimal entitlement policy design exacerbates the entanglements. Now, growth itself is imperiled, and much of the world risks sinking into a cold, watery sea of debt.

Drowning in Debt

To be clear, there is no requirement for a sovereign government, one that can print and tax in its own currency, to have a balanced budget. The United States has run a fiscal deficit almost every year of its existence and has zeroed out its debt only once, in 1835. When productivity is growing, it can make sense to borrow from the future to live better now with the expectation that it will be easier to pay the bill later. Our debt troubles aren’t about the existence thereof, but that it’s growing too fast at the hands of entitlement programs that governments are unwilling or unable to reign in.

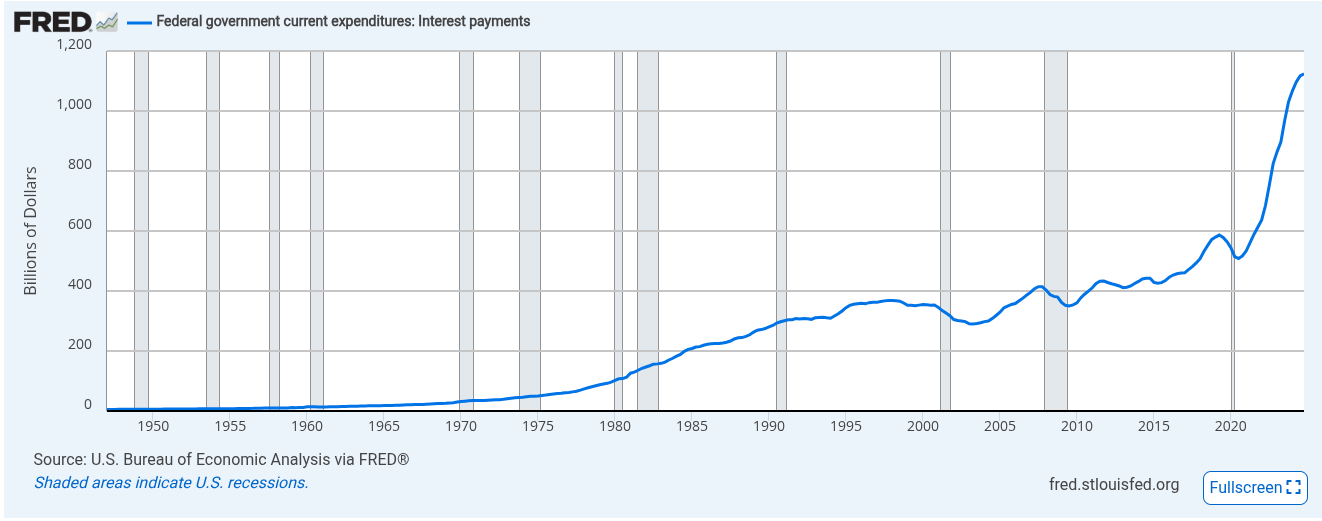

In many “developed” nations, the debt-to-GDP ratio is around 100 percent or more, similar to that of the mid-1940s, in the wake of heavy government spending needed to escape the Great Depression and win the Second World War. These kinds of debt levels are unsustainable, especially in a time of relative growth and peace. More worrisome, however, is not the total debt load but the cost of maintaining it. The United States now spends, for example, about 15 percent of its budget just making interest payments. The payments skyrocketed after 2020 to over $1 trillion annually by 2024, more than the US spends on defense.

Some falsely contend that public debt is not a problem because a sovereign government can always print more currency to pay it. Governments borrow money by selling bonds, mini loans that must be repaid later. Governments that cannot foster growth and raise productivity and/or spend beyond their means will eventually default on their debt. This need not be a “hard default” where bondholders take formal written losses. Instead, it could be its (ironically) worse cousin, a “soft default.” In a soft default, the debt is paid by printing worthless currency, literally inflating it away. Bondholders are not fooled either way; they will eventually stop lending.

Long before that happens, however, rising debt appears to choke off the growth required to pay it. Recent studies suggest a nonlinear relationship between public debt and economic growth, another “Kuznets Curve.” When debt levels are low, increasing the debt load (spending/cutting taxes) accelerates growth, but past a certain threshold, every new dollar of debt has the opposite effect, slowing growth. The reasons for this debt “hangover” effect are not fully understood. One theory is that government debt sales soak up capital that would otherwise go toward more productive uses; a kind of ‘zombification’ of the economy. This effect is similar to how government subsidies for “cost-disease” afflicted industries “lock in” low productivity.

As this “zombification” unfolds, politics becomes more salient. The beneficiaries of these policies become increasingly dependent on the elected officials who control those subsidies. The reverse also happens, however; elected officials become dependent on their campaign support. Hence, officials can only pay lip service to tackling the debt; real action requires slaughtering those sacred cows. For example, in the US, when the Republican party talks about deficit reduction, they refuse to touch the elephant in the room: Medicare, Social Security, and defense spending, line items which account for more than 80 percent of the projected deficit increase through 2032.

All they can do is rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic, to shift money and resources from productive to unproductive uses, leaving the deeper problem intact. As they do this, the socioeconomic structure becomes progressively less inclusive and more extractive, and the “social supercomputer” slows down. As debt levels worsen, rising servicing costs (interest) force policymakers to levy increasingly distortionary taxes before running into the deadweight loss “wall.” Deadweight loss, the hidden “tax on the tax,” grows to the square of the tax rate, meaning that past a certain point, we cannot tax our way out of a debt problem either. The cows must eventually be slaughtered.

Lifts and Nets

Entitlement programs now account for over half of Federal government spending, up from just a few percent a century ago. These line items are rapidly engulfing the Federal budget. Though the lines can be blurry, there are essentially two kinds of social welfare programs, metaphorically speaking, “lifts” and “nets.” “Lifts” are intended to uplift the beneficiary, while “nets” or “safety nets” are designed to catch them from falling too far when something goes wrong. “Lifts” include public education, perhaps universal childcare, and maybe one day, a UBI. I see these programs (when structured properly) as investments with huge payoffs.

However, any financial advisor worth his salt will advise you never to conflate an investment product with an insurance product. Life insurance is often structured in this manner, serving both purposes, albeit poorly. This is what makes our “safety nets” problematic. They are ostensibly intended to be a kind of social insurance. These programs should function like metaphorical trampolines, cushioning the impact of hard times and capturing the momentum to launch beneficiaries back upward. This is not, however, how they work in reality. Perhaps the term “safety net” is unintentionally fitting as many entitlement programs serve to catch and trap beneficiaries. We seem to have forgotten the purpose of insurance. “Insurance” is defined as:

The act of insuring, or assuring, against loss or damage by a contingent event; a contract whereby, for a stipulated consideration, called premium, one party undertakes to indemnify or guarantee another against loss by certain specified risks.

Insurance is risk sharing. A “premium” is paid to a payee, either a company or government entity, which in return agrees to indemnify the payor for contingent losses if they occur. Note the words “indemnify” and “contingent,” for they are crucial to a proper understanding of insurance. Indemnify and contingent are defined as follows:

Indemnify:

To make restitution or compensation for, as for that which is lost; to make whole; to reimburse; to compensate

Contingent:

Happening by or subject to chance or accident; unpredictable

The principle of indemnification holds that the insurer must make the subscriber “whole” in the event of a chance loss. It’s the reason, for example, when you “total” your 2005 Honda in a car accident, your insurer will not issue you a check to buy a new replacement Honda. Instead, they will compensate you for the vehicle’s value depreciated by usage and time. Insurers are bound to this principle because if they paid the original purchase price, the claimant would be “bettered” by the loss, incentivizing more car accidents. It’s also the reason you cannot buy insurance to fund a new vehicle; that’s an investment function, not a contingent loss.

Entitlement Entanglements

Understanding the core principles of insurance, it should be no wonder why modern societies are going bankrupt at the hands of “safety nets.” Retirement, for example, isn’t truly a “contingent” event; it is a goal or aspiration, yet we try to insure it as if it were an accident and wonder why the trust funds run dry. Note that we can insure against people outliving their nest egg, but this is a fundamentally different function. Tackling dry trust funds requires splitting the investment element of retirement from the insurance element. The same is happening with healthcare, where benefits are now used to pay for routine check-ups and other “non-contingent” treatments. As we will discuss in the next section, health insurance must return to its roots of compensating individuals only for serious injuries and illnesses.

Unemployment insurance (UI) schemes, ostensibly designed to bridge employment gaps, too often subsidize unemployment itself. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, many employers found it extremely difficult to find staff because the UI payments offered were higher than the incomes received when working; it “bettered” the unemployed, incentivizing people to quit. Many UI schemes also adopt laughably weak “job search” requirements that ask beneficiaries to prove they are actively looking for a new job to remain eligible. This is easily gamed by beneficiaries who send out quick online job applications as “evidence” that they are searching, while bureaucrats turn the other cheek.

We know reform is possible. The Floridian UI system became insolvent in 2009 after the Great Recession. Subsequent reforms of the system indexed the benefits to economic KPIs. During periods of high unemployment, subscribers would have more time to find work and less in times of economic strength. Georgia followed a similar path after its UI system became insolvent in 2009, also indexing UI benefits to economic conditions in 2012. States that index UI benefits returned workers to employment nearly twice as fast as non-reform states.

In addition, “Disability insurance” (DI) in the United States has morphed into an oft-abused early retirement program. Despite research finding that at least 20 percent of DI beneficiaries can return to work, they rarely do. I suspect this is a gross undercount. DI applications and awards spike fourfold during economic recessions. There is no reason to believe that people become disabled 4 times faster after losing their jobs. Indeed, some US states have actively pushed their UI beneficiaries to apply for disability, even to the point of establishing “call centers” complete with agents to help them file applications. They do this because it’s cheaper for the state; every person who can transition from UI to DI transfers the social liabilities to the Federal government.

DI abuse is a uniquely challenging problem because the rise of recipients is also a consequence of the changing nature of work. When work required physical labor, a physician could, more or less, objectively assess one’s ability to remain working. As the nature of work has become more cognitive, impairments have become less tangible and more subjective. Furthermore, disability classifications are outmoded. Whether or not you are disabled is as much a function of your education level as it is your health. It is presumed, for example, that a college graduate with back pain can continue working whereas a high school graduate cannot because the latter cannot obtain an “office” job. This simply isn’t true anymore, if it ever was.

Furthermore, when one government agency grants a benefit, it tends to automatically unlock many others, including eligibility for free/reduced-price food, internet, housing, and other subsidized benefits. Not to mention a litany of private benefits, from cheaper gym memberships and train rides to movie tickets. The consequence is “betterment,” which obviates the intended function of these programs, catching and trapping beneficiaries, leaving them hopelessly dependent on public money and elected officials unwilling to do anything about it except rearrange the deck chairs.

The government can and should provide a basic social safety net for its citizens, it should also invest in “lifts” to uplift and better its population. It must take care, however, not to conflate these functions, for it will encourage dependency and create perverse incentives that are harmful to everyone. We will discuss how to do this in the next section. Until this is done, however, if it is not obvious already, it soon will be: the waters are rising, and there are no lifeboats.

You may also like….

Considering current mess, barely imagine effects of UBI...

For all that boomers sneer at Millenials and Zoomer as 'entitled' just watch at how their eyes bulge, spittle forms, and veins pop when you point out their entitlements, created by endebting their grandchildren, are creating a mess.