Risk & Progress| A hub for essays that explore risk, human progress, and your potential. My mission is to educate, inspire, and invest in concepts that promote a better future. Subscriptions are free, paid subscribers gain access to the full archive, including the Pathways of Progress and Realize essay series.

In our discussion of wealth, knowledge, and what we call “material progress,” it is worth pausing and asking: what does this all matter anyway? We commonly measure economic growth using a metric known as Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, but few of us stop and think about what GDP truly measures. For the cynical, GDP growth represents the expansion of human greed and environmental destruction. For those who understand the origins of human progress, however, GDP is anything but destructive. The GDP metric is an imperfect but reasonably good indicator of material progress and human capability.

A Brief History of GDP

GDP is a metric born out of a World War 2 need to determine the total productive capacity of an economy to support a war effort. The metric was never intended to be a measure of well-being for the inhabitants of that economy. Nonetheless, its cousin, GDP per capita, or the GDP divided by the total population, has become commonly used to measure well-being. There are three ways to measure Gross Domestic Product. You can calculate the total output of the economy, the total expenditures within the economy, or all of the incomes. Measuring total expenditures is the most familiar and understandable method for most of us. This calculation follows the formula below:

GDP = Consumer Spending + Investment Spending + Government Spending + (Exports-Imports)

In practice, this simple calculation is fraught with fuzziness and error. Adding up the sales of tangible goods, for example, is relatively easy, but intangible services are notoriously difficult to calculate. This is salient because our economies are gradually dematerializing, requiring fewer material inputs as an ever-greater share of the productive capacity is devoted to intangible services. This makes calculations of economic growth increasingly difficult as economies develop and mature.

Criminal activity, such as illicit drug sales, alongside the shadow economy, have to be indirectly estimated by reviewing police reports and crime statistics. Meanwhile, household services, such as child-rearing by parents, are entirely ignored by statisticians. A famous paradox exemplifies this problem: a widower lowers GDP when he marries his former housekeeper because he no longer needs to pay her a wage. Partly, this is a matter of convenience because there is no agreement about how to measure the value of those services. Nevertheless, the OECD estimates that unpaid and uncounted household services account for an average of 15 percent of GDP, meaning that our economies are probably under-sized in economic reporting.

GDP also fails to capture quality and technological improvements of goods and services over time. Televisions, for example, have trended larger, lighter, more energy efficient, and thinner, with improvements to color and resolution. The value of these improvements will not show up in GDP data. Nor do statisticians capture the value of that which is free. The free access to information on Wikipedia or the cornucopia of websites, apps, videos, and music made by creators online, certainly has value but cannot be fully captured in economic data.

The Easterlin Paradox

Given the difficulty of calculation, should we consider GDP a reliable indicator of growth or progress? Many contend that we should not, noting that GDP growth doesn’t improve reported happiness or contentment. Researcher Richard Easterlin used survey data from people in various countries, asking them questions about subjective well-being. He found that at a point in time, general happiness varies with income between and within countries, but over time happiness does not trend upward as incomes rise. This means that while higher-income individuals are typically happier than lower-income individuals, higher incomes don't produce greater happiness over time. This has become known as the Easterlin Paradox; the contradiction between the point-of-time and time-series findings in the research.

Attempting to explain this contradiction, researchers have suggested that perhaps beyond a certain level of GDP per capita, enough to satisfy the basic material needs of clothing, housing, and food, further wealth did not improve well-being. Instead, beyond this level, respondents looked past their absolute income and instead toward their relative income when answering surveys about life satisfaction. These findings have profound implications. If rising incomes do not raise subjective well-being, it is argued, that there may be no purpose in economic growth at all. Indeed, this idea has already become ingrained in the public psyche. Many today believe that past a basic level of material satisfaction continued growth only serves to feed the greed of the wealthy…the primary beneficiaries of yawning inequality.

Others have challenged Easterlin’s conclusions. Research, conducted by Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers takes advantage of a wider breadth and depth of data than was available to Easterlin. They conclude that, at least in most countries, there is no paradox; the relationship between material progress and well-being is quite robust. Stevenson and Wolfers compared respondents’ answers to questions of subjective well-being to the log of GDP per capita using data from some 131 countries. They found a positive correlation that exceeded 0.8 and no evidence of a satiation point beyond the level of GDP per capita needed to satisfy basic material needs.

Their research revealed apparent errors in survey questions used in prior studies. For example, while surveys from Japan initially appeared to confirm the Easterlin Paradox, Stevenson and Wolfers found that survey response categories were changed multiple times in the 1960s, distorting the results. When they accounted for that change, reported life satisfaction rose sharply in the 1950s and 1960s, then more slowly in the 1970s and 1980s, before beginning to fall in the 1990s, roughly mirroring the performance of the Japanese economy.

This analysis, however, relied on a log scale for GDP per capita. As noted by

, “a constant increase on that scale gives exactly the type of curve represented on the graph of the Easterlin paradox." So we cannot discount Easterlin’s research wholesale. Additionally, Easterlin’s overall conclusions conform with what we know about human psychology. As Page also illustrates:Feelings of happiness are signals guiding our everyday decisions, both big and small. Our hedonic system—the cognitive processes that generate these feelings—has been shaped by evolution to help us make decisions that enhance our survival and reproduction.5 A key feature of these signals is that they only reflect deviations relative to expectations. Positive surprises produce good feelings, while negative surprises result in bad feelings.

What we describe as “happiness” can only be fleeting as satisfaction inevitably resets to a new baseline. The literature supports this “hedonic treadmill,” as psychologists Brickman and Campbell coined it. A study comparing the surveyed happiness of paraplegics with lottery winners and a control group, for instance, revealed little difference in relative happiness. Indeed, despite huge increases in material well-being for most Americans since the 1940s, reported happiness and satisfaction have remained relatively consistent.

In these circumstances, social comparisons have become the basis for a “deviation” that indicates relative happiness. Page also notes that, paradoxically, economic growth can sometimes make people less satisfied. When East Germany reunified with the West, for instance, the material well-being of the East soared, but it also revealed the yawning gap with the West. As Easterners compared themselves with the West, they reported lower satisfaction. This is all to say that happiness or satisfaction isn’t the proper benchmark for measuring progress or growth in the first place.

HDI: An Alternative

Some thinkers, such as Amartya Sen, believe that we ought to measure growth and human progress using a “capabilities approach,” which emphasizes the ends (a decent standard of living) over the means (GDP per capita). Under this framework, poverty is not merely the deprivation of financial resources but rather the deprivation of the capability to live a good life. “Growth” therefore, is understood to be the expansion of the opportunities and capabilities available to individuals.

For example, while a fasting person has the same nutritional state as one who is starving, we would not treat them identically disadvantaged; the latter has no capability to eat, as opposed to the former. In response to this thinking, the UN developed an alternative measure of growth known as the Human Development Index or HDI. The HDI compiles several proxies for human capabilities, including life expectancy, school enrollment, literacy, and yes, GDP per capita. This, it is argued, better accounts for actual human progress than a rough measure of gross economic production.

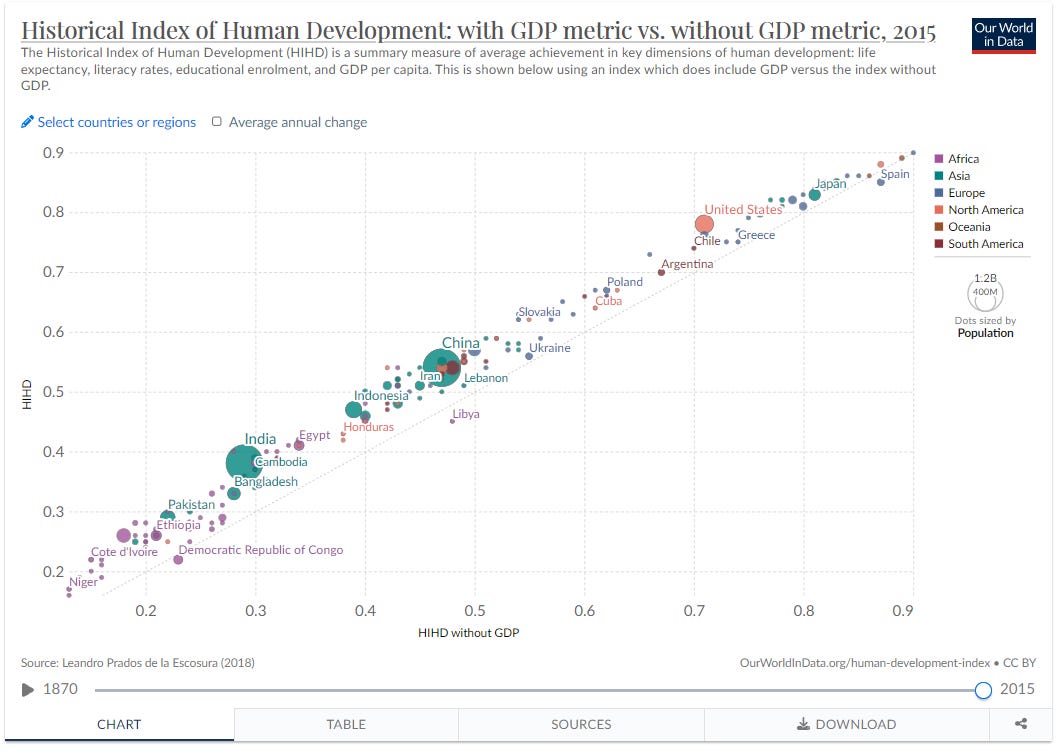

HDI tracks GDP per capita rather well, a fact that shouldn’t be surprising because GDP forms a component of the index. But what happens when we remove GDP from the index entirely and focus solely on its non-monetary components? To the surprise of many, HDI performance doesn’t change much; GDP per capita and HDI are still robustly correlated. Thus, for all of its shortcomings, GDP is a reasonably good indicator of human progress and prosperity. This is likely because of the positive feedback loop between capability and material growth. Material growth, the growing stock of human knowledge, begets greater human capability and opportunity, which is seized by individuals who beget additional growth, and so on.

Implications for Progress

For all of its fuzziness in measurement, GDP remains among the best metrics of material progress currently available to us. Subjective measures of human satisfaction are distorted by the hedonic treadmill and social comparisons while other measures, like HDI closely track GDP anyway. As Diane Coyle wrote in her book, GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History:

To be poor is to have little choice available, and the increase in possibility is the most important aspect of escaping from poverty. On this view, economic development is a combination of increasing individual capacities…and increasing range of opportunities…Economic development is an increase in freedom.

This all means that contrary to the popular social narrative, economic growth is not merely a shallow measure of material greed, but a key, if imperfect, performance indicator for society, progress, and human well-being. Nonetheless, as an indicator of progress, GDP too breaks down across long time scales. Measurement and data challenges make estimating historical GDP difficult and even when we can, it may still fail to fully capture the true scope of human progress. To truly understand progress over long periods, we must turn to more fundamental measures of progress, including the Social Development Index, discussed next.

You May Also Like…

I would go one level deeper to GDP per hour worked. If GDP remained the same but hours worked fell by half, you would probably be twice as happy. At least you would have much more time to devote to other activities.

Absolutely loved this essay!! You couldn't have further stressed the importance of economic growth that drives long term prosperity for the society and mankind.